This album was created by a member of the TPS Teachers Network, a professional social media network for educators, funded by a grant from the Library of Congress. For more information, visit tpsteachersnetwork.org.

Coralie Franklin Cook – Suffragette, Activist, and Educator

Album Description

Topics:

The Women's Suffrage Movement

Coralie Franklin Cook

The tension between African American women and White women during the Women's Suffrage Movement

The 19th Amendment

Learners: 6th graders

6 - 8

6 - 8  Social Studies/History

Social Studies/History  Grade 6

Grade 6  Women's Suffrage Movement

Women's Suffrage Movement  Women's Suffrage

Women's Suffrage  19th Amendment

19th Amendment  Coralie Franklin Cook

Coralie Franklin Cook  Virginia

Virginia  Suffragette

Suffragette  Activist

Activist  Educator

Educator

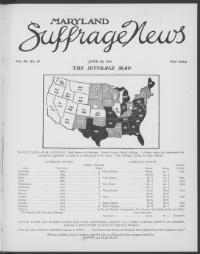

Maryland suffrage news., June 26, 1915, Image 1

Teaching Notes

Map showing the progression of states allowing women to vote in the United States.

Reference note

Newspaper: Maryland suffrage news. (Baltimore, Md.) 1912-1920Newspaper Link: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn89060379/1915-06-26/ed-1/seq-1

Image provided by: University of Maryland, College Park, MD

PDF Link: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn89060379/1915-06-26/ed-1/seq-1.pdf

Coralie Franklin Cook: A Famous Suffragist, Speaker, and Baha’i

Teaching Notes

"

An African American woman, who was born into enslavement, later became a famous public speaker, inspiring suffragist, and devoted Baha’i. Learn about the life of Coralie Franklin Cook.

Coralie Cook’s Background, Family, and Career

Coralie Cook was born in 1861 in Lexington, Virginia to enslaved parents, Albert and Mary Elizabeth Edmondson Franklin.

She was a great-granddaughter of Brown Colbert — the grandson of Elizabeth Hemings, the matriarch of the enslaved Hemings family at President Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. Elizabeth Hemings was the mother of Sally Hemings — the famous enslaved woman who was impregnated at least six times by her enslaver, Thomas Jefferson, who was 30 years older than her.

In 1880, Coralie became the first known descendant of people enslaved by Thomas Jefferson to earn a college degree when she graduated from Storer College in Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia. She taught English and elocution at Storer College and purchased her own home from the college in 1884 when she was just 23 years old.

She later moved to Washington D.C. and became a faculty member at Howard University. She was the Chair of Oratory at Howard and taught elocution there. That’s where she met her husband, George Cook.

Like Coralie, her husband, George, was born into slavery in Winchester, Virginia, in 1855. He managed to escape from slavery, attend school, and graduate from Howard University with a bachelor’s degree in 1886 and a law degree in 1898. He was the Professor of Commercial and International Law and the Dean of the School of Commerce and Finance. Coralie and George got married on August 31, 1898, and had one son, George William Cook Junior.

In addition to teaching at Howard University, Coralie was the second woman of color to be appointed by the judges of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia to the Board of Education. She held this position for 12 years — the longest term held by any board member. She was also the director of the Home for Colored Children and Aged Women and a member of the Red Cross, the Juvenile Protective Society, and the NAACP.

Coralie Cook’s Work As A Famous Writer, Speaker, and Suffragist

Coralie was an ardent activist, dedicated to obtaining equal rights for women, especially the right to vote.

RELATED: In Pursuit of Equality: 100 Years of Women’s Suffrage

As Abdu’l-Baha, one of the central figures of the Baha’i Faith, said at a talk at a women’s suffrage meeting in New York in 1912:

The most momentous question of this day is international peace and arbitration, and universal peace is impossible without universal suffrage.

In a talk in Paris, he addressed how:

the female sex is treated as though inferior, and is not allowed equal rights and privileges. …Neither sex is superior to the other in the sight of God. Why then should one sex assert the inferiority of the other, withholding just rights and privileges as though God had given His authority for such a course of action?

He also spoke about the unique and vital role that mothers have in society:

In the necessity of life, woman is more instinct with power than man, for to her he owes his very existence.

If the mother is educated then her children will be well taught. When the mother is wise, then will the children be led into the path of wisdom. If the mother be religious she will show her children how they should love God. If the mother is moral she guides her little ones into the ways of uprightness.

It is clear therefore that the future generation depends on the mothers of today.

In her editorial, “Votes for Mothers,” published by the NAACP magazine, “The Crisis,” Coralie wrote:

Mothers are different, or ought to be different, from other folk. The woman who smilingly goes out, willing to meet the Death Angel, that a child may be born, comes back from that journey, not only the mother of her own adored babe, but a near-mother to all other children. As she serves that little one, there grows within her a passion to serve humanity; not race, not class, not sex, but God’s creatures as he has sent them to earth.

It is not strange that enlightened womanhood has so far broken its chains as to be able to know that to perform such service, woman should help both to make and to administer the laws under which she lives, should feel responsible for the conduct of educational systems, charitable and correctional institutions, public sanitation and municipal ordinances in general. Who should be more competent to control the presence of bar rooms and ‘red-light districts’ than mothers whose sons they are meant to lure to degradation and death? Who knows better than the girl’s mother at what age the girl may legally barter her own body? Surely not the men who have put upon our statute books, 16, 14, 12, aye be it to their eternal shame, even 10 and 8 years, as ‘the age of consent!’

If men could choose their own mothers, would they choose free women or bondwomen? …I transmit to the child who is bone of my bone, flesh of my flesh and thought of my thought; somewhat of my own power or weakness. Is not the voice which is crying out for ‘Votes for Mothers’ the Spirit of the Age crying out for the Rights of Children?

Coralie was a founding member of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs and a member of the National American Women’s Suffrage Association. Coralie, who was recognized nationally as an excellent public speaker, was the only African American woman who was invited to speak at Susan B. Anthony’s 80th birthday party in 1900.

However, she had spent so much of her life advocating for the rights of women and women of color and had grown disappointed by white women’s reluctance to work with Black women within the suffrage movement. Disheartened that the movement had, in her words, “turned its back on the woman of color” and did not view the rights of African American women as a priority, Coralie expressed her grievances in her speech.

…no woman and no class of women can be degraded and all womankind not suffer thereby.

Coralie said, “…And so Miss Anthony, in behalf of the hundreds of colored women who wait and hope with you for the day when the ballot shall be in the hands of every intelligent woman; and also in behalf of the thousands who sit in darkness and whose condition we shall expect those ballots to better, whether they be in the hands of white women or Black, I offer you my warmest gratitude and congratulations.”

She would later refuse to participate in white-dominated suffragist organizations and activities and became very active in the fight against Jim Crow laws.

As author and college professor Paula Giddings wrote, “Throughout their history, Black women also understood the relationship between the progress of the race and their own feminism. Women’s rights were an empty promise if Afro-Americans were crushed under the heel of a racist power structure. In times of racial militancy, Black women threw their considerable energies into that struggle—even at the expense of their feminist yearnings.”

Coralie Cook’s Life As a Baha’i and Racial Justice Activist

Coralie and George learned about the Baha’i Faith in 1910 and became Baha’is in 1913. In the Baha’i Faith, racism is regarded as “the most vital and challenging issue” confronting the United States.

RELATED: 5 Inspirational Baha’i Women in American History

Coralie and George organized Baha’i events at Howard University, including one talk by Abdu’l-Baha, and they even won awards for their social welfare work in the African American community.

In a letter she wrote to Abdu’l-Baha in 1914, she described how egregious racism was in the U.S.:

Knowledge of the progress of the colored people during their fifty years of freedom has astounded the world and incited the envy and hatred of those who prophesied their extinction and argued their inability to work for themselves.

In the midst of unfriendly surroundings they have accumulated $7,000,000,000 worth of property raising a million and a half of dollars in the past year alone for educational work, coming out of slavery with 95 percent of their whole number unable to read or write to say that number is reduced to only 30 percent an advance surpassing that of the whites during the same period.

Instead of this marvelous achievement appealing to all that is best and noblest in the whites, it has seemed to have a contrary effect. Laws are being passed in many sections compelling colored people to live in segregated districts, where they have had handsome houses among white residences these houses have been attacked, lives endangered, valuable property ruthlessly destroyed, anonymous orders to vacate, if ignored, have even resulted in the use of dynamite and total destruction of a house and its contents, the Law Courts offer no redress for the word of a black man is not taken against that of a white man where Judge and Jury are all of the dominant class.

She believed that the Baha’i teachings are “not only the last hope of the colored people, but must appeal strongly to all persons regardless of race or color…” So, she encouraged Baha’is to “stand by the teachings though it requires superhuman courage…”

She worked for racial justice and taught the oneness of humanity until she passed away in 1942. What a remarkable woman in our history to look up to."

Coralie Franklin Cook

Teaching Notes

- "Description

- Coralie Franklin Cook was born into slavery in Lexington, Virginia, in 1861, a descendent of the Hemings family that was enslaved by Thomas Jefferson. She was a trained educator, a noted public speaker, a community leader, and a suffragist. Franklin Cook graduated from Storer College in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, in 1880. She studied and went on to teach English and Elocution at Storer from 1882 to 1893. She married Geore William Cook, a professor at Howard University. Cook went on to teach at Howard as well and later the Washington Conservatory of Music. Active in civic life in Washington, DC, she was the second Black woman to serve on the District of Columbia Board of Education, serving for twelve years.

An early participant in clubs for Black women in the DC area, Coralie Franklin Cook was a founder of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) formed in 1896. Women’s suffrage was an important issue for the NACW but not its single focus. Suffrage was viewed as means to improve lives of all Black people living in segregation and linked to ensuring voting rights for Black men who were disenfranchised through literacy tests, poll taxes, and grandfather clauses.

She was also a member of the National American Women Suffrage Association (NAWSA), the dominant suffrage organization in the United States. While the NAWSA admitted Black women, they held conventions in which Black women were excluded and forced Black women to march separately in suffrage parades. Cook was the only Black woman invited to speak at Susan B. Anthony’s 80th birthday celebration in 1900. She offered her disappointment in the lack of concern for Black women’s rights stating, “...no woman and no class of women can be degraded and all women kind not suffer thereby.”

In 1915, Coralie Franklin Cook wrote a piece entitled “Votes for Mothers” in a suffrage-themed issue of the NAACP magazine, the Crisis. Although questioning the focus on the motherly role of women, Cook noted that the ability to “make and administer the laws under which she lives” would assist women in their maternal duties. She further emphasized suffrage for women of color noting that, “Disfranchisement [sic] because of sex is curiously like disfranchisement because of color. It cripples the individual, it handicaps progress, it sets a limitation upon mental and spiritual development.”

Cook lived to see the passage of the 19th amendment in 1920 and continued to serve her DC community"

Black women suffragists holding sign reading "Head-Quarters for Colored Women Voters," in Georgia

Reference note

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. (1910 - 1920). Black women suffragists holding sign reading "Head-Quarters for Colored Women Voters," in Georgia Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/09740960-d940-0136-3dde-3d48f083c992

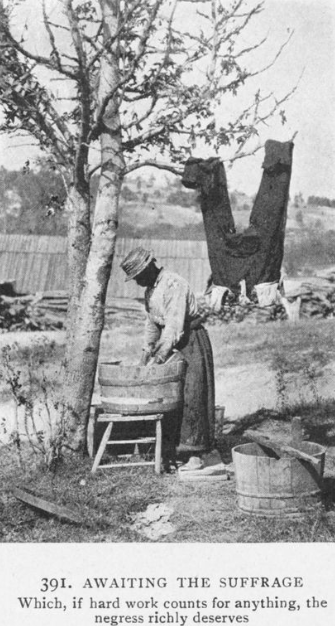

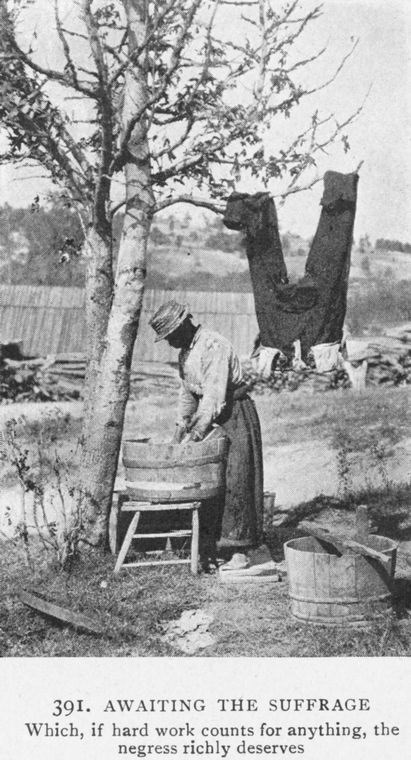

Awaiting the suffrage; Which, if hard work counts for anything, the Negress richly deserves.

Reference note

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library. (1910). Awaiting the suffrage; Which, if hard work counts for anything, the Negress richly deserves. Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-9493-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Between Two Worlds: Black Women and the Fight for Voting Rights

Teaching Notes

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Was there ever a time when your voice wasn’t being heard?

During the 19th and 20th centuries, Black women played an active role in the struggle for universal suffrage. They participated in political meetings and organized political societies. African American women attended political conventions at their local churches where they planned strategies to gain the right to vote. In the late 1800s, more Black women worked for churches, newspapers, secondary schools, and colleges, which gave them a larger platform to promote their ideas.

But in spite of their hard work, many people didn’t listen to them. Black men and white women usually led civil rights organizations and set the agenda. They often excluded Black women from their organizations and activities. For example, the National American Woman Suffrage Association prevented Black women from attending their conventions. Black women often had to march separately from white women in suffrage parades. In addition, when Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony wrote the History of Woman Suffrage in the 1880s, they featured white suffragists while largely ignoring the contributions of African American suffragists. Though Black women are less well remembered, they played an important role in getting the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Amendments passed.

Library of Congress, Lot 12572, https://www.loc.gov/item/93505051/

Black women found themselves pulled in two directions. Black men wanted their support in fighting racial discrimination and prejudice, while white women wanted them to help change the inferior status of women in American society. Both groups ignored the unique challenges that African American women faced. Black reformers like Mary Church Terrell, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, and Harriet Tubman understood that both their race and their sex affected their rights and opportunities.

Because of their unique position, Black women tended to focus on human rights and universal suffrage, rather than suffrage solely for African Americans or for women. Many Black suffragists weighed in on the debate over the Fifteenth Amendment, which would enfranchise Black men but not Black women. Mary Ann Shadd Cary spoke in support of the Fifteenth Amendment but was also critical of it as it did not give women the right to vote. Sojourner Truth argued that Black women would continue to face discrimination and prejudice unless their voices were uplifted like those of Black men.

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1900. http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-70ac-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a9

African American women also believed that the issue of suffrage was too large and complex for any one group or organization to tackle alone. They hoped that different groups would work together to accomplish their shared goal. Black suffragists like Nannie Helen Burroughs wrote and spoke about the need for Black and white women to cooperate to achieve the right to vote. Black women worked with mainstream suffragists and organizations, like the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

However, the mainstream organizations did not address the challenges faced by Black women because of their race, such as negative stereotypes, harassment, and unequal access to jobs, housing, and education. So in the late 1800s, Black women formed clubs and organizations where they could focus on the issues that affected them.

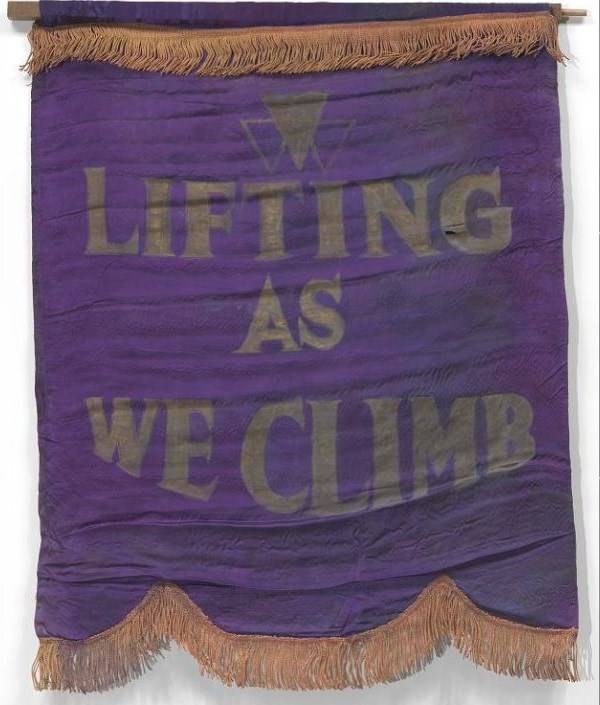

Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

In Boston, Black reformers like Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin and Charlotte Forten Grimke founded the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) in 1896. During their meetings at the Charles Street Meeting House, members discussed ways of attaining civil rights and women’s suffrage. The NACW’s motto, “Lifting as we climb,” reflected the organization’s goal to “uplift” the status of Black women. In 1913, Ida B. Wells founded the Alpha Suffrage Club of Chicago, the nation's first Black women's club focused specifically on suffrage.

After the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified in 1920, Black women voted in elections and held political offices. However, many states passed laws that discriminated against African Americans and limited their freedoms. Black women continued to fight for their rights. Educator and political advisor Mary McLeod Bethune formed the National Council of Negro Women in 1935 to pursue civil rights. Tens of thousands of African Americans worked over several decades to secure suffrage, which occurred when the Voting Rights Act passed in 1965. This Act represents more than a century of work by Black women to make voting easier and more equitable.

LBME3-037a, Lane Brothers Commercial Photographers Photographic Collection, 1920-1976. Photographic Collection, Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library.

http://digitalcollections.library.gsu.edu/cdm/ref/collection/lane/id/1580

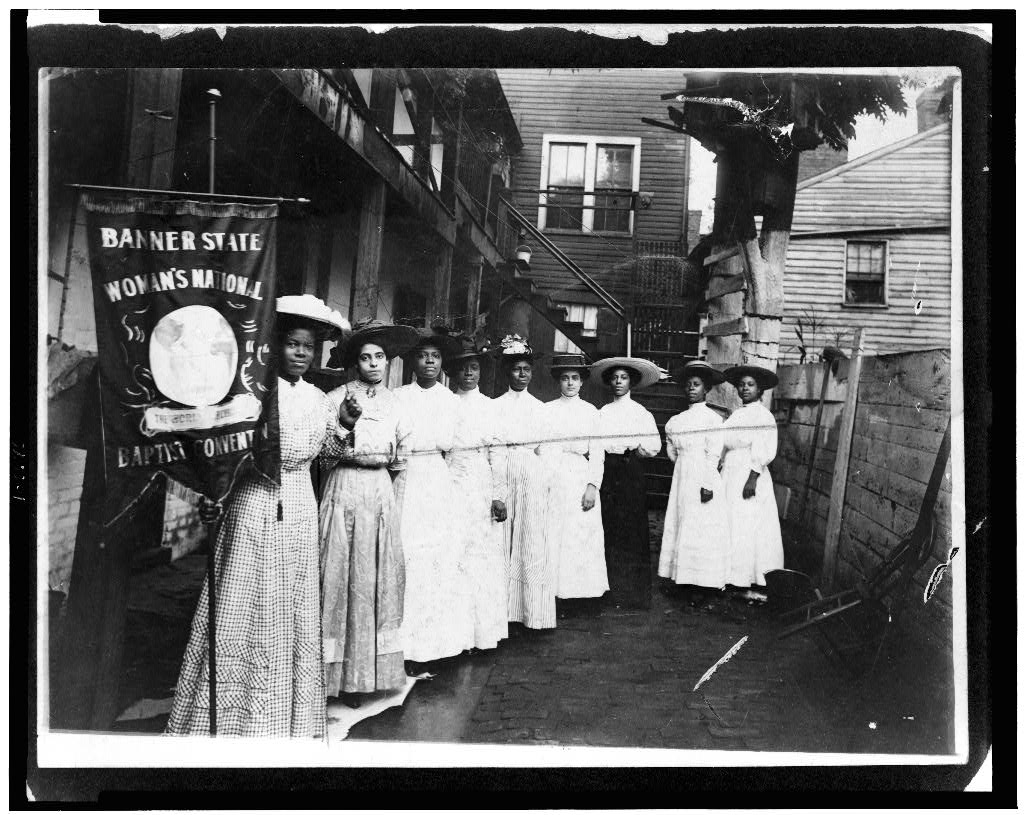

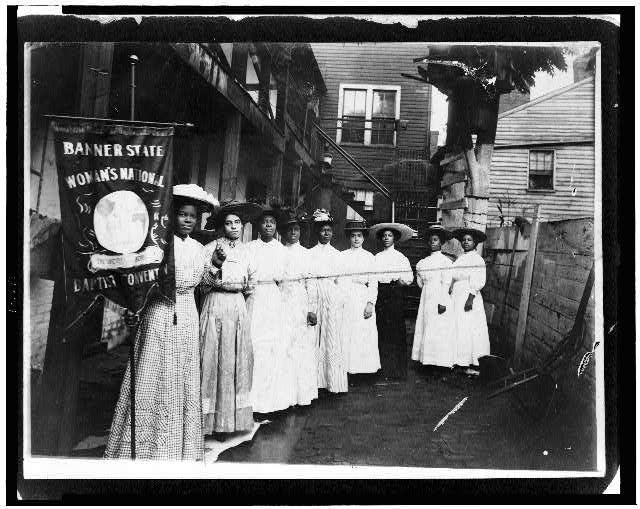

[Nine African-American women posed, standing, full length, with Nannie Burroughs holding banner reading, "Banner State Woman's National Baptist Convention"]

Teaching Notes

African American Women fighting for their right to vote.

Reference link: http://www.loc.gov/item/93505051/

Reference note

Created / Published

- [between 1905 and 1915]

Genre

- Group portraits--1900-1920

- Portrait photographs--1900-1920

- Photographic prints--1900-1920

Notes

- - Title devised by Library staff.

Repository

- Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print

Digital Id

- ds 13272 //hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ds.13272

- cph 3c06646 //hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c06646

Coralie Franklin Cook “Child of Storer”

Teaching Notes

"

Family Enslaved by Thomas Jefferson

Coralie Franklin Cook, Storer teacher and pioneering civil rights leader was a descendant of Elizabeth Hemmings — matriarch of the Hemmings family. The Hemmings family were both enslaved by and related to Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States.First in Her Family

In 1880, Coralie Franklin Cook was the first recorded descendant of people enslaved by Jefferson to graduate from a higher learning school. She was part of the first generation of children to graduate from Storer Normal School, noted as a true “child” of Storer College. While attending Storer Normal School, Cook showed talent for the written and oral studies for which she would be known for later.Before even graduating Storer, Cook taught in a small schoolhouse in Knoxville, Maryland, just a few miles outside of Harpers Ferry. Cook later joined Storer as the first female elocution teacher in 1881. Teachers working with newly freed people taught students of all ages and with various skill levels. Most students struggled to learn how to read, write, and do arithmetic—something that enslaved people could not legally do before the Civil War and emancipation.

"Much harder to learn one’s letters at thirty than at six"

Cook shared her empathy and sadness for her students’ struggles in a summary for the school’s annual report:“[It] is much harder to learn one’s letters at thirty than at six; harder to understand long division at forty than at eight; and harder still to put one’s pride in the pocket, and go day after day into classes with those so much younger. It is at such times as these that the unbidden tears rush into your eyes, as you guide the untutored hand in forming letters, and think, 'O, how willingly would I learn for you, if I could.' But they do learn. I cannot tell you how many came to us last fall unable to write their names, who, when they left in the spring, could write a letter. There is one thing of which I am certain. The problem of Negro education has been solved, and Storer Normal School is helping with the demonstration.”

Just a few years later, in 1885, in correspondences to the Missionary Helper, Cook noted her pleasure in “The wonderful improvement in everyday life that Christianity and education are making among the people. The need of schools like ours is greater, if possible than ever before. It belongs, to the graduates of these institutions to go forth waging war against the great mass of illiteracy and the South which threatens to be an evil second only the that of slavery itself.”

Grace, Skill and Power

Cook’s reputation as a talented speaker and educator at Storer College transcended beyond Harpers Ferry. Fellow civil rights pioneer (and brother-in-law) J.R. Clifford commented on her skills as a “master of this inestimable blessing” and John Wesley Cromwell, an editor for the People’s Advocate in Washington, DC as “an elocutionist of grace, skill and power.”Suffrage and Civil Rights

Her schooling and work at Harpers Ferry helped shape her for larger civil rights activism combating the lack of equality for all Black people, and especially for Black women.Her achievements include: editor of the “Women’s Column” for the Pioneer Press, founder and president of the Mount Hope Woman’s Christian Temperance Union at Harpers Ferry, teaching English and elocution at Howard University, part founder of National Association of Colored Women, superintendent of the National Home for Destitute Colored Women and Children amongst others.

"On behalf of the thousands who sit in darkness"

Cook was the only woman of color invited to speak at Susan B. Anthony’s 80th birthday. She spoke on “behalf of hundreds of colored women who wait and hope with you on the day when the ballot shall be in the hands of every intelligent woman; and also in behalf of the thousands who sit in darkness and whose condition we shall expect those ballots to better, whether they be in the hands of white women or black…”.Enduring love for Storer College

Throughout all her endeavors, Storer College would be a place of deep love and appreciation for Cook, “There’s a heart to heart life there [at Storer] that I at least, have never found anywhere else”.Cook bridged a gap between White and Black Suffragists, learn more"

Coralie Franklin Cook Image

Iowa State University Archives of Women's Political Communication: Coralie Franklin Cook

Teaching Notes

"Coralie Franklin Cook was an African American suffragist, orator and scholar.

Descended from a woman enslaved by President Thomas Jefferson, Cook was born in Lexington, Virginia, in 1861 to Albert and Mary Elizabeth Edmondson Franklin. She graduated from Storer Normal School in 1880. After a few years of teaching at her alma mater, she moved to Washington, D.C., and served as the head of the Home for Colored Orphans and Aged Women for five years. In 1899, she married George William Cook, an academic and NAACP member, and joined the faculty at Howard University. Cook became the second Black woman appointed to the D.C. school board, the first being fellow suffragist Mary Church Terrell.

Cook was also a prominent figure in the suffrage movement, co-founding the National Association of Colored Women and joining the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Cook wrote many editorials for the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis, advocating for woman suffrage and criticizing white women’s treatment of Black women in the suffrage movement.

Cook died on August 25, 1942.

Brodgon, Danielle, Breanna Makonnen, Makiah Lyons, Karla Knight-Valdry, Sharilyn Clark, and Kieori Gethers. Biographical Sketch of Coralie Franklin Cook. Alexandria, VA: Alexander Street, 2019. https://search.alexanderstreet.com/view/work/bibliographic_entity%7Cbibliographic_details%7C4064720.

“African American Women Leaders in the Suffrage Movement.” Turning Point Suffragist Memorial. Turning Point Suffragist Memorial Association. Accessed January 27, 2020. https://suffragistmemorial.org/african-american-women-leaders-in-the-suffrage-movement/."

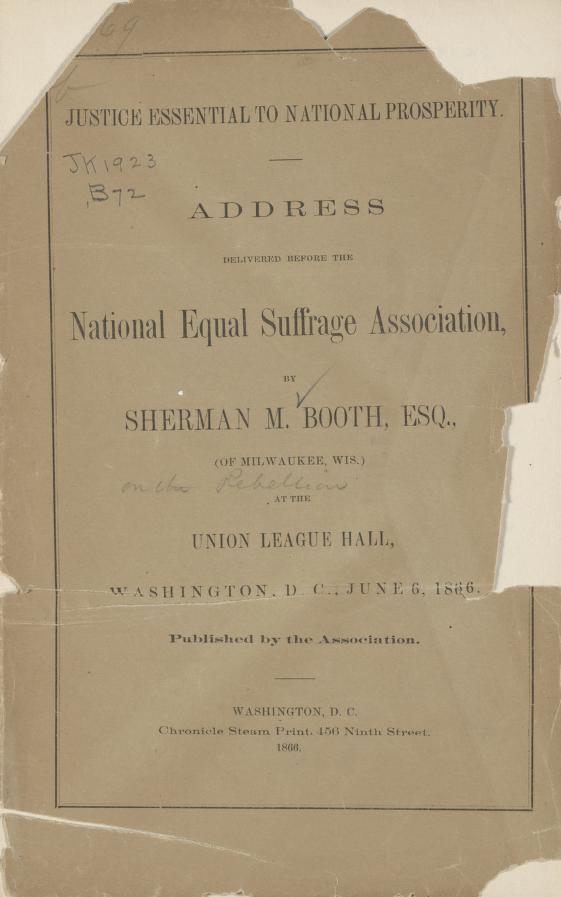

Justice essential to national prosperity. Address delivered before the National equal suffrage association,

Teaching Notes

Advocates for impartial suffrage, for all.

Reference link: http://www.loc.gov/item/09032790/

Reference note

Created / Published

- Washington, D.C., Chronicle steam print, 1866.

Notes

- - Also available in digital form.

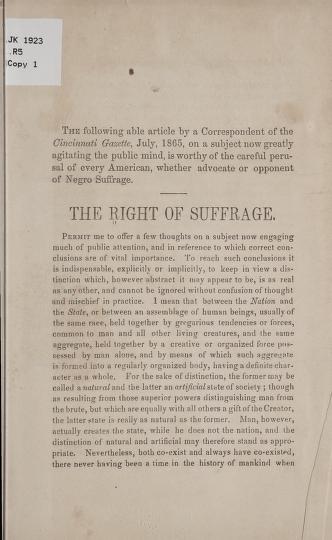

The Right of suffrage.

Teaching Notes

Discusses the feelings surrounding black women also participating in the women's suffrage movement.

Reference link: http://www.loc.gov/item/43032137/

Reference note

Created / Published

- [Cincinnati? : s.n., 1865?]

Notes

- - At head of title: The following article by a correspondent of the Cincinnati gazette, July, 1865, on a subject now greatly agitating the public mind, is worthy of the careful perusal of every American, whether advocate or opponent of Negro suffrage.

- - Also available in digital form.

Mary Church Terrell Papers: Speeches and Writings, 1866-1953; 1920, June 24 , Remarks Made at the Dunbar High School in Complimenting Mrs. Coralie Franklin Cook

Teaching Notes

Remarks made about Coralie Franklin Cook and her excellent work on the D.C Board of Education

Reference link: http://www.loc.gov/item/mss425490407

Reference note

Genre

- Manuscripts

Repository

- Manuscript Division

Digital Id

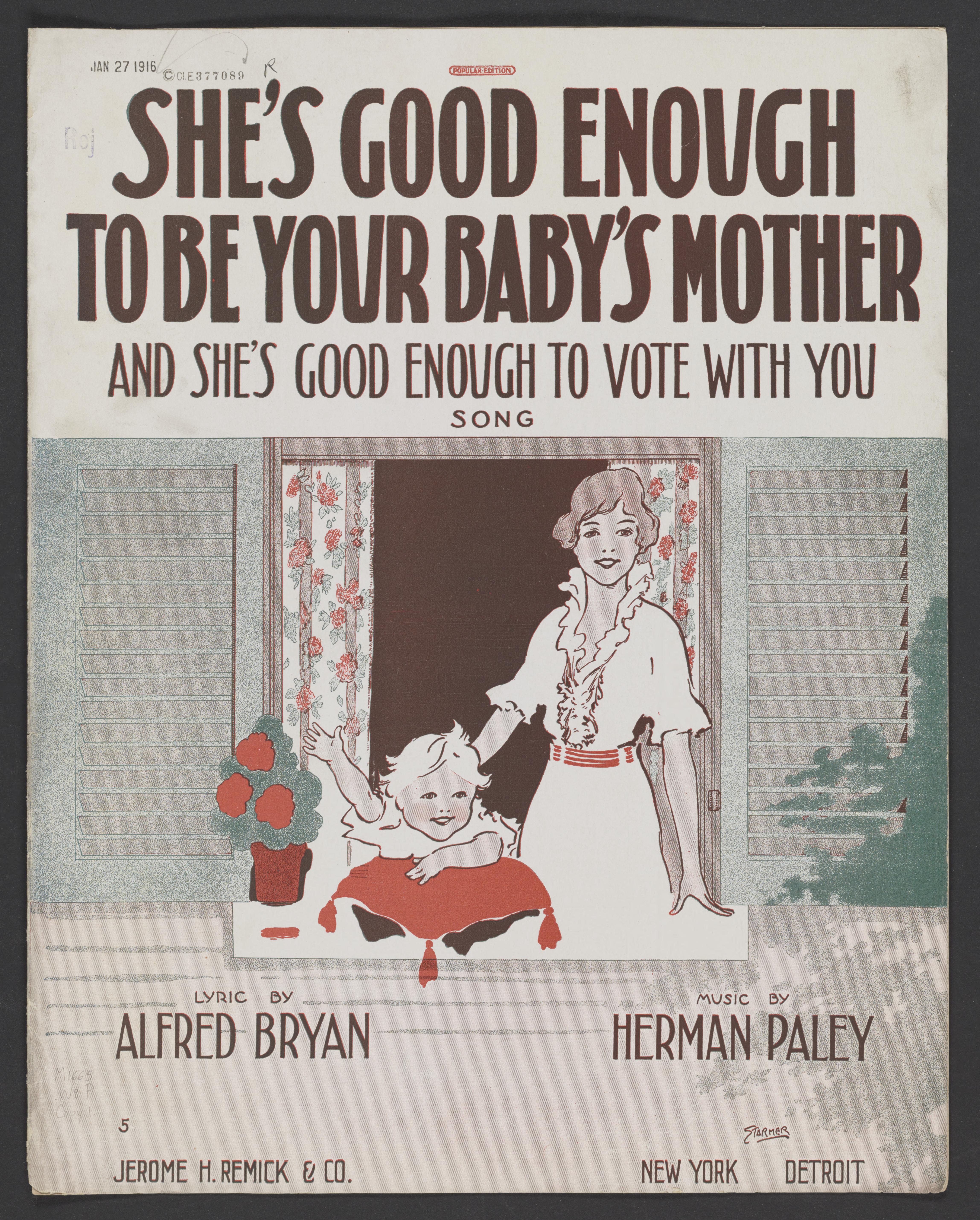

Image 1 of She's good enough to be your baby's mother and she's good enough to vote with you : song

Teaching Notes

Primary Source to have students observe.

Reference link: http://www.loc.gov/resource/mussuffrage.mussuffrage-100123?r=-1.169,-0.102,3.337,1.383,0

Reference note

Created / Published

- New York : Jerome H. Remick & Co., [1916]

- ©1916

Genre

- Songs

- Scores

Notes

- - E377089 U.S. Copyright Office 19160127

- - For voice and piano.

- - Color illustration depicts mother with happy baby.

- - Includes advertisements for other music.

- - Staff notation.

Digital Id

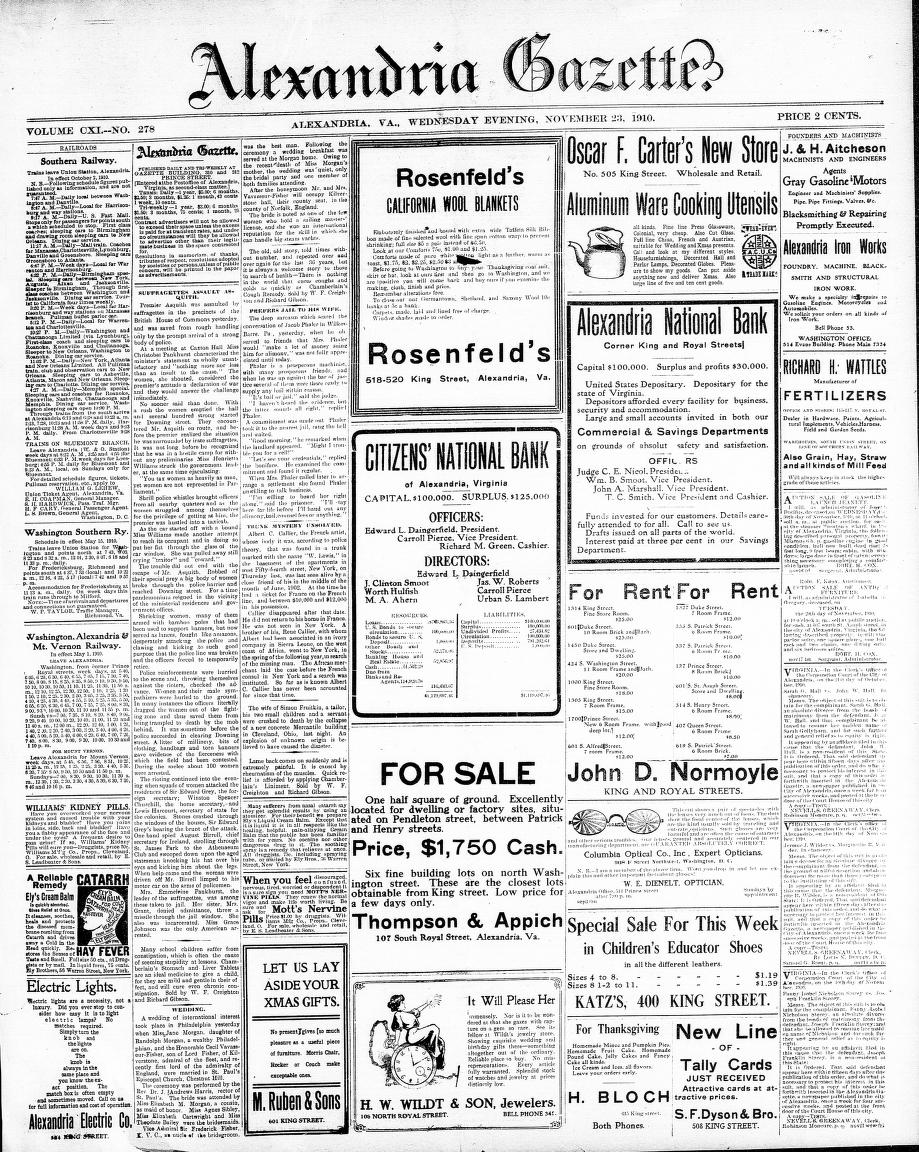

Image 1 of Alexandria gazette (Alexandria, D.C.), November 23, 1910

Teaching Notes

Clipping from Newspaper that specifically talks about suffragettes in VA.

Reference link: http://www.loc.gov/resource/sn85025007/1910-11-23/ed-1/?sp=1&q=black+suffragettes&clip=874,2083,1238,5630&ciw=1024&rot=0

Reference note

Created / Published

- Alexandria, D.C., November 23, 1910

Genre

- Newspapers

Notes

- - Daily (except Sunday)

- - Vol. 34, no. 3516 (Jan. 1, 1834)-v. 191, no. 55 (Aug. 6, 1974).

- - Publisher varies: Alexandria Gazette Corp., <1926>-<1974>.

- - President/editors: C.C. Carlin, <1900>-<1966> ; Sarah S. Carlin [Messer], <1966>-<1974>.

- - Issues for Jan. 1, 1834-Dec. 31, 1839 also called new ser., v. 10, no. 3516-v. 14, no. 8061.

- - Suspended May 25, 1861-May 12, 1862; Nov. 1-Dec. 30, 1864.

- - Also issued on microfilm from the Library of Congress, Photoduplication Service.

- - Archived issues are available in digital format as part of the Library of Congress Chronicling America online collection.

- - Triweekly eds.: Alexandria gazette (Alexandria, D.C. : 1825), <1825-1838> ; Alexandria gazette (Alexandria, Va. : 1872), <1872->.

- - Issued from the same office during the suppression of the Alexandria gazette by Union forces: Local news (Alexandria, Va.), Oct. 7, 1861-Feb. 10, 1862.

- - Supplement: Potomac news (Potomac, Va.), Sept. 2, 1926-Jan. 26, 1928.

- - Supplement: Alexandria gazette teen topics, Oct. 31, 1961-May 9, 1962.

- - Gazette (Alexandria, Va.) (DLC)sn 94060016 (OCoLC)30575741

Image 1 of Alexandria gazette (Alexandria, D.C.), November 23, 1910

Teaching Notes

References suffragettes in Virginia.

Socialism, feminism, and suffragism : the terrible triplets, connected by the same umbilical cord, and fed from the same nursing bottle

Teaching Notes

It depicts how suffragettes were viewed.

Suffragettes at Capitol, 1913

Teaching Notes

Notice and Wonder

Reference link: http://www.loc.gov/resource/npcc.19161/

Reference note

Created / Published

- 1913.

Genre

- Glass negatives

Notes

- - Title from unverified data provided by the National Photo Company on the negative or negative sleeve.

- - Gift; Herbert A. French; 1947.

- - General information about the National Photo Company collection is available at http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.npco

- - This glass negative might show streaks and other blemishes resulting from a natural deterioration in the original coatings.

- - Temp. note: Batch four.

Repository

- Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print

Digital Id

- npcc 19161 //hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/npcc.19161

Women Win the Vote!: 19 for the 19th Amendment By: Nancy B. Kennedy

Reference note

Kennedy, N. B. (2020). Women Win the Vote! 19 for the 19th Amendment. WW Norton. https://www.amazon.com/Women-Win-Vote-19th-Amendment/dp/1324004142#detailBullets_feature_div

Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All By Martha S. Jones

Reference note

Jones, M. S. (2020). Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All. Basic Books. https://www.amazon.com/Vanguard-Black-Barriers-Insisted-Equality/dp/1541618610#detailBullets_feature_div

Book: African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850–1920 By:Rosalyn Terborg-Penn

Teaching Notes

Coralie Franklin Cook (1902)

Teaching Notes

A newspaper article announcing Coralie Franklin Cook would be giving a lecture soon.

Details highlight her, her upbringing, and her accomplishments.

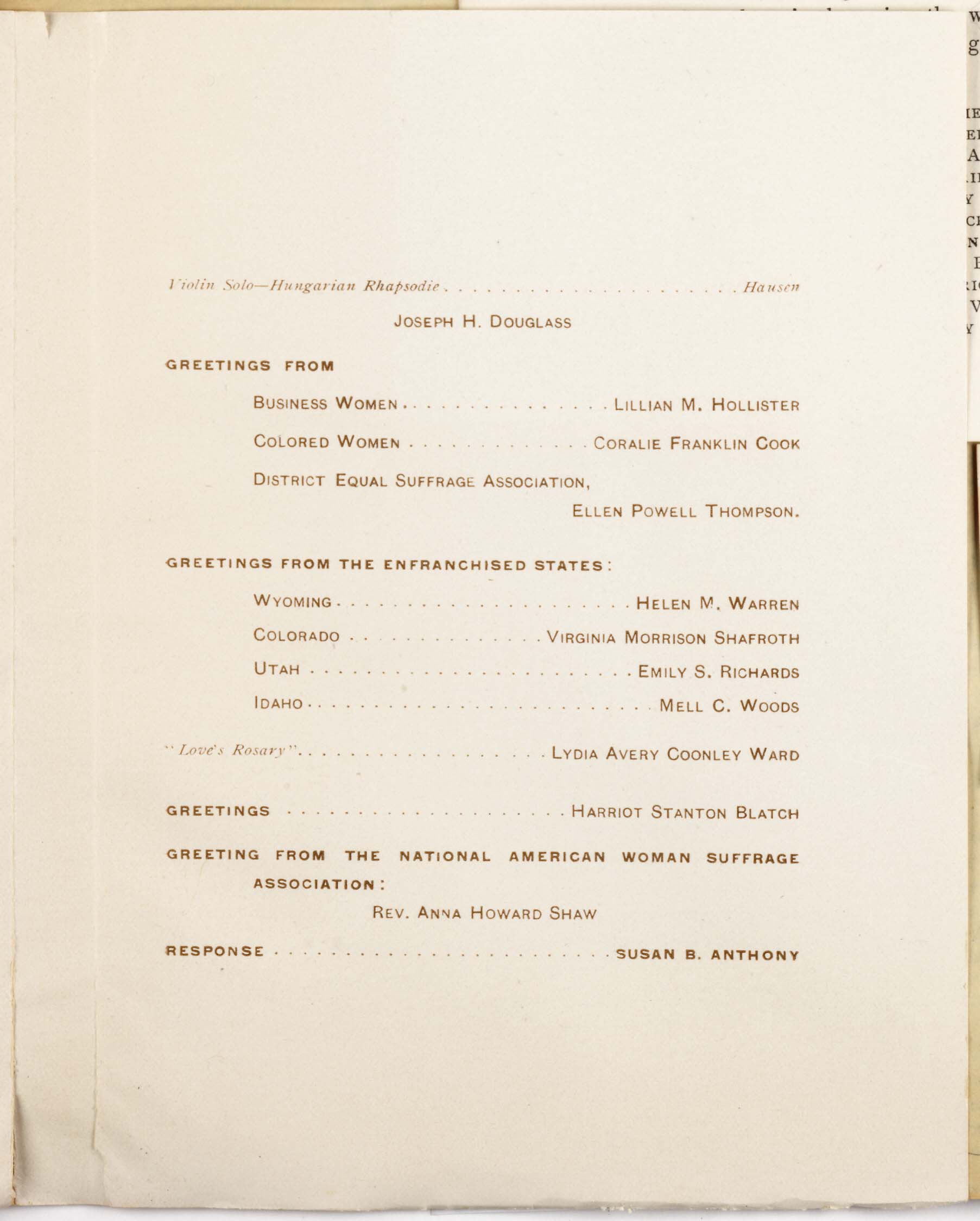

Image 3 of Susan B. Anthony, 1820-February 15-1900; Eightieth birthday celebration

Teaching Notes

Coralie Franklin Cook was the only African American Woman asked to speak at Susan B. Anthony's birthday party in 1900.

Reference link: http://www.loc.gov/resource/rbcmil.scrp1006203/?sp=3&st=image

Reference note

Created / Published

- 15-Feb-00

Genre

- Programs

Notes

- - Lists speakers, birthday celebration committee, Wm Lloyd Garrison poem to Susan B. Anthony

Repository

- Rare Book And Special Collections Division

Digital Id