This album was created by a member of the TPS Teachers Network, a professional social media network for educators, funded by a grant from the Library of Congress. For more information, visit tpsteachersnetwork.org.

Historiography and Supporting the Historical Read

Album Description

The Library of Congress’ online collections are an ideal “sandbox of inquiry” where students can engage in historical thinking, not through a packet of documents, but in an accessible online setting ideal for exploration. This album explores how Library of Congress collections and Teaching with Primary Sources resources (including the TPS Teacher’s Network) can be leveraged to design curriculum which supports student understanding of historiography and engagement in the historical read.

Background:

Historians are concerned with constructing a truthful account of the past, with reference to the sources available and the inquiry questions asked (Appleby et al., 1994). Research investigating the cognitions of historians indicates that historians use their purpose and theory of history when analyzing and interpreting sources as evidence, a cognitive process which Leinhardt and Young (1994) call the historical read. Despite the central place of this cognition to the procedural thinking of historians, historical thinking curriculums rarely engage students in the historical read. Instead, source work is often presented as an isolated skills activity designed to support student evaluation of the reliability of pre-selected source documents, rather than their usefulness in answering inquiry questions relative to a frame of interpretation (Evers et al., 2025). Such activities can distort student conceptions of evidence and truth in history and leave students ill-prepared to navigate the complexities of historical representation in school and everyday life. While historical accounts may clash on the basis of “biased” factual inaccuracies, history is inherently positioned and accounts differ due to different interpretations of the significance of sources, events, and perspectives from the past (Jenkins, 1991, King, 2020, Low-Beer, 1967). When engaging in the historical read, historians draw on differing theoretical commitments and methodological approaches to interpret sources and construct historical accounts. The historical read is deeply related to historiography, or the ways in which historians have interpreted sources and constructed accounts of the past across time (Popkin, 2021). Despite their central place in the historical discipline, historiography and historical methodologies are overlooked in K-12 curricula (Marcyk et al., 2022). The questions arises: how can the Library’s online collections and TPS educational resources support teachers in the challenging task of instructing students in historiography and engaging them in the historical read? By creating this album, I hope to answer this question. I look forward to the feedback and ideas of others in the Network as I begin my exploration!

Guiding Quotes

Historical read invokes the interpretive stance assumed by historians, which includes their global sense of historical purpose and their theory of history. Different historians have different notions of the purpose of history... Different historians also have different theoretical positions. For example, a Marxist historian, a feminist historian, and an economic historian, each constructing explanatory narratives of the same series of events, would emphasize different aspects. (Leinhardt and Young, 1996, p.449)

Students of history should be exposed to historical texts of all kinds, diverse primary documents as well as the interpretive narrative accounts constructed from them. These texts should be vibrant, positioned, and moving rather than anemic, neutral, and dull and should have a clear historical voice and stance. … From the discovery that texts are positioned, we expect students to see that history is interpretive, to understand that historians have intentions and theories, and eventually to develop their own historical stance and sense of historical purpose (Leinhardt and Young, 1996, p. 480).

Aims:

- Introduce students to diverse historical methodologies and the concepts of academic and “popular” historiography

- Facilitate students’ analysis of how academic and popular historiography shape our understanding of the past, supporting their awareness of themselves and their world as situated in time and asking the question, "Why this historical narrative now?"

- Support student development of a disciplinary conception of evidence

- Support students’ selection and analysis of sources through multiple frames, developing their understanding of the interpretive nature of history and importance of historiographical knowledge to the historians’ craft

Audience: Secondary History and Social Science educators

Readings/Resources:

Popkin, J. D. (2020). From Herodotus to H-Net: The story of historiography (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190077617.001.0001

Teaching History "What have historians been arguing about?"

References:

- Evers, S., Hicks, D., & Shelburne, S. (2025). Whose historical thinking? Representation of women in the Digital Inquiry Group’s Reading Like a Historian world history curriculum. Theory & Research in Social Education, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2025.2469495

- Jenkins, K. (1991). Rethinking history. Routledge.

- King, L. J. (2020). Black history is not American history: Toward a framework of Black Historical Consciousness. Social education, 84(6), 335-341.

- Leinhardt, G., & Young, K. (1996). Two texts, three readers: Distance and expertise in reading history. Cognition and Instruction, 14(4), 441–486. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3233783

- Low-Beer, A. (1967). Moral judgments in history and history teaching. In Burston, W.H. & Thompson, D. (Eds.). Studies in the Nature and Teaching of History. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Marczyk, A. A., Jay, L., & Reisman, A. (2022). Entering the historiographic problem space: Scaffolding student analysis and evaluation of historical interpretations in secondary source material. Cognition and Instruction, 40(4), 517–539. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2022.2042301

6 - 8

6 - 8  9 - 12

9 - 12  Social Studies/History

Social Studies/History  historiography

historiography

Case: Topics in 8th grade Civics- Citizenship & Mexican deportations during the Great Depression

Teaching Notes

I am working with a practicing teacher to create curriculum that incorporates historical inquiry into an 8th grade Civics class. The teacher is interested in engaging students in reading across sources, including sources in archives and collections and academic texts. He believes incorporating historical instruction into Civics education can help students develop a nuanced understanding of the constructed and changing nature of Civic institutions. Students will investigate topics like due process, climate change, and citizenship through different interpretive lenses such as: indigenous perspectives on history, political history, history from below, and women's and gender history.

As a starting point, he would like to create a historical inquiry about Mexican deportations during the Great Depression to use when teaching about citizenship. In this post, I will explore how Library of Congress online collections can support this inquiry.

Lesson outline:

This lesson is a teacher-led introduction to selecting sources from loc.gov. The teacher will guide students step-by-step through the process of source location and selection, employing a “think aloud” strategy to model the historical read of historians working from different theoretical and methodological approaches. Completed as a whole group, students will use the collected information to answer the Essential Question: How do accounts of Mexican Deportation during the Great Depression differ depending on the approach to interpretation used by the historian?

In later lessons, students will be given more autonomy in the process of research. We plan to select subjects with robust and easy to find collections like the U.S. Civil Rights movement. As part of our project we will adapt scholarly descriptions of historical methodologies (like those below) to be appropriate for a middle school student.

Lesson Topic: Deportation during the Great Depression

Essential Question: How do accounts of Mexican Deportation during the Great Depression differ depending on the approach to interpretation used by the historian?

Search criteria: 1929-1939 (Great Depression), Mexican immigrants, Mexican-Americans, Immigration, Relocation, Deportation

Depression and the Struggle for Survival was used as a starting place for this activity. Sources were selected by exploring related items to the sources included in the article.

|

Source(s) |

Methodology/theoretical approach |

Rationale for selection of source for method/frame |

Inquiry question(s) |

|

Not Identified, and Robert Hemmig. Group of children posing under sign that reads "U.S. Department of Agriculture Farm Security Administration Farm Workers Community". California El Rio, 1941. El Rio, California. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/toddbib000400/. Delano, Jack, photographer. Topeka, Kansas. Two Mexican workers employed at the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railroad locomotive shops. Topeka Shawnee County United States Kansas, 1943. Mar. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017847207/. |

History from below Approach to historical interpretation “History from below seeks to take as its subjects ordinary people, and concentrate on their experiences and perspectives, contrasting itself with the stereotype of traditional political history and its focus on the actions of 'great men'. It also differed from traditional labour history in that its exponents were more interested in popular protest and culture than in the organisations of the working class” (The Institute of Historical Research, 2008).

|

These sources show working people and children, two groups left out of “great man” historical narratives. Rather than study immigration and deportation through the actions of those enacting deportations through policies, these sources can be used to investigate the experiences of the working people who were relocated. |

What was life like for Mexican workers who were relocated during the Great Depression? What kind of jobs did Mexican immigrants do during the Great Depression? Did their job experience change during the Great Depression? Why might Mexican workers have been targeted for deportation during the Great Depression? How did they respond to deportation?

|

|

Lange, Dorothea, photographer. Mexican migrant woman harvesting tomatoes. Santa Clara Valley, California. United States California Santa Clara County Santa Clara Valley, 1938. Nov. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017770798/. Lange, Dorothea, photographer. Ranch camp for pea pickers. Near Milpitas, Santa Clara County, California. United States Santa Clara County California, 1939. Apr. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017771835/. |

Indigenous Perspective Approach to historical interpretation Historical interpretation centers around the central theme of the relationship between humans and the land and non-humans, the local landscape is an expression of both time and place, and a circular conception of time (Marker, 2011). |

These sources depict the landscape upon which Mexican immigrants lived and worked. They show Mexican workers interacting with the landscape during the food production process. |

What was the relationship between farm owners, farm workers, and the landscape during the Great Depression? What parts of the United States did Mexicans travel and relocate to? How did the land change due to farming in the early 20th century? What kind of agricultural practices/food ways were used prior to this time period? Who lived on the farm land before it was owned by the farmers and lived on by migrant/immigrant workers? What wildlife was present in the areas in these photos? How did the animals lives change due to farming? |

|

Lange, Dorothea, photographer. Privy in cheap migratory camp. San Joaquin Valley, California. United States California San Joaquin Valley, 1936. Nov. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017769626/.

Russell, Lee, photographer. Mexican women separating meat from shells. Pecan shelling plant. San Antonio, Texas. 1939. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division. https://www.loc.gov/resource/cph.3c30262/ Guide to Pecan Worker's Strike Lange, Dorothea, photographer. Mexicans entering the United States United States immigration station, El Paso, Texas. El Paso United States El Paso County Texas, 1938. June. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017770594/. |

Women’s and gender history Approach to historical interpretation · “Women-oriented: The experiences of women are valued and researched. Multiple gender perspectives are used to construct historical narratives. Gender as a category for historical analysis: Historical investigation asks questions about the relationship between gender and power. Historical narratives represent women as active agents whose experiences are important to the study of the past. · Gender as a geographic and historical construction: Historical investigation examines how gender is defined across time, culture, and place. Historical narratives do not represent gender identity as static or universal concepts. · Spatial analysis of the intersection of race and gender: Historical investigation asks questions about the gendered dynamics of cross-cultural encounters and includes analysis of the intersection of race and gender” (Evers et al., 2025, p.8). |

These sources depict women. They showcase cross-cultural encounters between women and Americans through their depiction of the immigrant experience. |

What kind of jobs did Mexican immigrants to America work during the Great Depression? Did men and women work together at job sites during the Great Depression? Did they work the same type of jobs? How did gender roles differ in Mexico and the United States during the early 20th century? |

Reference link: https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/

Take Chances, Get Messy, and Make Mistakes! Scaffolding Student Source Selection on loc.gov

Teaching Notes

In this post, I explore ideas for scaffolding student selection of sources which are "vibrant, positioned, and moving" (Leinhardt & Young, 1996, p.480). During TPS Leadership course, my peers and I discussed the value of:

- "failing" to locate sources,

- experimenting with different searching procedures, and

- an exploratory, organic, and iterative approach to research.

1.  Rebecca Ward

reminisced about "wikiracing" in her younger days and wondered if the game could be adapted for the loc.gov collections. In the original wikiracing game, students try to navigate from an initial topic to a goal topic by clicking on blue links within Wikipedia. The game required students to deduce how topics might be connected, finding a trail between topics through connections like geography or time period. What might this look like in the Library's online collections and how can it increase student familiarity with the site and encourage exploration?

Rebecca Ward

reminisced about "wikiracing" in her younger days and wondered if the game could be adapted for the loc.gov collections. In the original wikiracing game, students try to navigate from an initial topic to a goal topic by clicking on blue links within Wikipedia. The game required students to deduce how topics might be connected, finding a trail between topics through connections like geography or time period. What might this look like in the Library's online collections and how can it increase student familiarity with the site and encourage exploration?

Procedure:

- Instruct students to use an Advanced Google Search to find a source in the Library archives that represents them in some way. Debrief the Google search feature and it's affordances.

- Introduce the Library collections' global search features. Explain that students will be playing a game where they are tasked with connecting their original source to a source about a different topic of study by clicking on blue links ONLY. No search bar allowed!

- On your marks, get set, go! Students race to connect their source to a source about the selected topic.

- Reflection and Processing: Instruct students to free write about their experience searching the archives. How difficult was it to find a source about the targeted topic? What strategies did you use? What did you see along the way? Did you get distracted by something interesting? List three sources/pages you would like to revisit. Facilitate a class discussion about the process and co-construct a list of search procedures.

2.  Subarna Basu

shared ideas for searching with young learners, including a search strategy bookmark with spaces for students to fill in with "what do I want to learn," "what words will I type in the search bar," and "what do I see." This strategy, leveled for k-2 learners, helps students make a research plan and evaluate search results for their usefulness to the inquiry.

Subarna Basu

shared ideas for searching with young learners, including a search strategy bookmark with spaces for students to fill in with "what do I want to learn," "what words will I type in the search bar," and "what do I see." This strategy, leveled for k-2 learners, helps students make a research plan and evaluate search results for their usefulness to the inquiry.

3. Search strategies:

Library of Congress Global Search

Use the format selection menu to select a type of primary source (e.g. map, photograph, etc.). Once your results list appears, use the filters in the left menu to narrow your search by date, location, collection, exhibit, or access availability.

Advanced Google Search

Type your search term followed by site:loc.gov to limit your Google search to the Library of Congress website. (Note: there is no space after site:) Reminder: searching Google without limiting to loc.gov results in items from across the internet.

4. National History Day Guidance for Finding Sources in the Library of Congress online archives (grades 6-12):

Reference link: https://guides.loc.gov/student-resources

Historical Methodologies Jigsaw using Library of Congress Research Guides

Teaching Notes

Students are often left out of the process of source selection. The Library of Congress research guides can be an important scaffold in student selection of sources and development of contextual information.

A case example of this activity is presented in another album entry.

Learning activity: Historical Methodologies Jigsaw

Step 1: Introduce students to the concept that historians use different methodologies to interpret the past (e.g., history from below, political history, cliometrics )

Step 2: Select a subject for investigation from the Library's research guides. Guide students in the creation of inquiry questions that would be of interest to a historian using a specific historical methodology to study the historical topic. The Question Formulation Technique can be used to scaffold this step.

*Guiding question for selecting a subject in the research guide: Does this subject guide include multiple sources for students to observe/read, evaluate, and select for use in a historical inquiry?

Step 3: Using the research guide for the subject as a starting place, instruct students to select 2-3 primary and secondary sources that would help a historian working from their methodological lens to answer their inquiry questions.

Step 4: Scaffold students' analysis of their selected sources in relation to the questions developed during Step 2.

Step 5: Jigsaw students using different methodologies together, have them compare the questions asked, sources selected, and answers constructed from analysis.

Step 6 (Reflection and Processing): Lead a whole group discussion about how a historian's approach to research impacts what we know about the past. Discuss why it is important for historians to draw from multiple methodologies when interpreting the past. Whose perspectives are emphasized in the various approaches to interpretation? Whose are missing?

Question to ponder:

In addition to related archival sources, the research guides include secondary accounts of many historical topics written by Library staff and links to online publications and books about the topics. In a college classroom, the books listed in research guides might become the starting point of an annotated bibliography and historiographical essay assignment. How can we reimagine these historiography learning activities for k-12 learners?

Readings/Resources:

Making History "Themes and Approaches to the Discipline"

New American History "Why History Matters" This teaching resource offers upper high school students a primer on historiography and historical methods

Silence in the Archives: Women's History & Primary Sources Network Album This album explores how the questions we ask shape the history we tell.

Reference link: https://guides.loc.gov/

Working with Secondary Sources

Teaching Notes

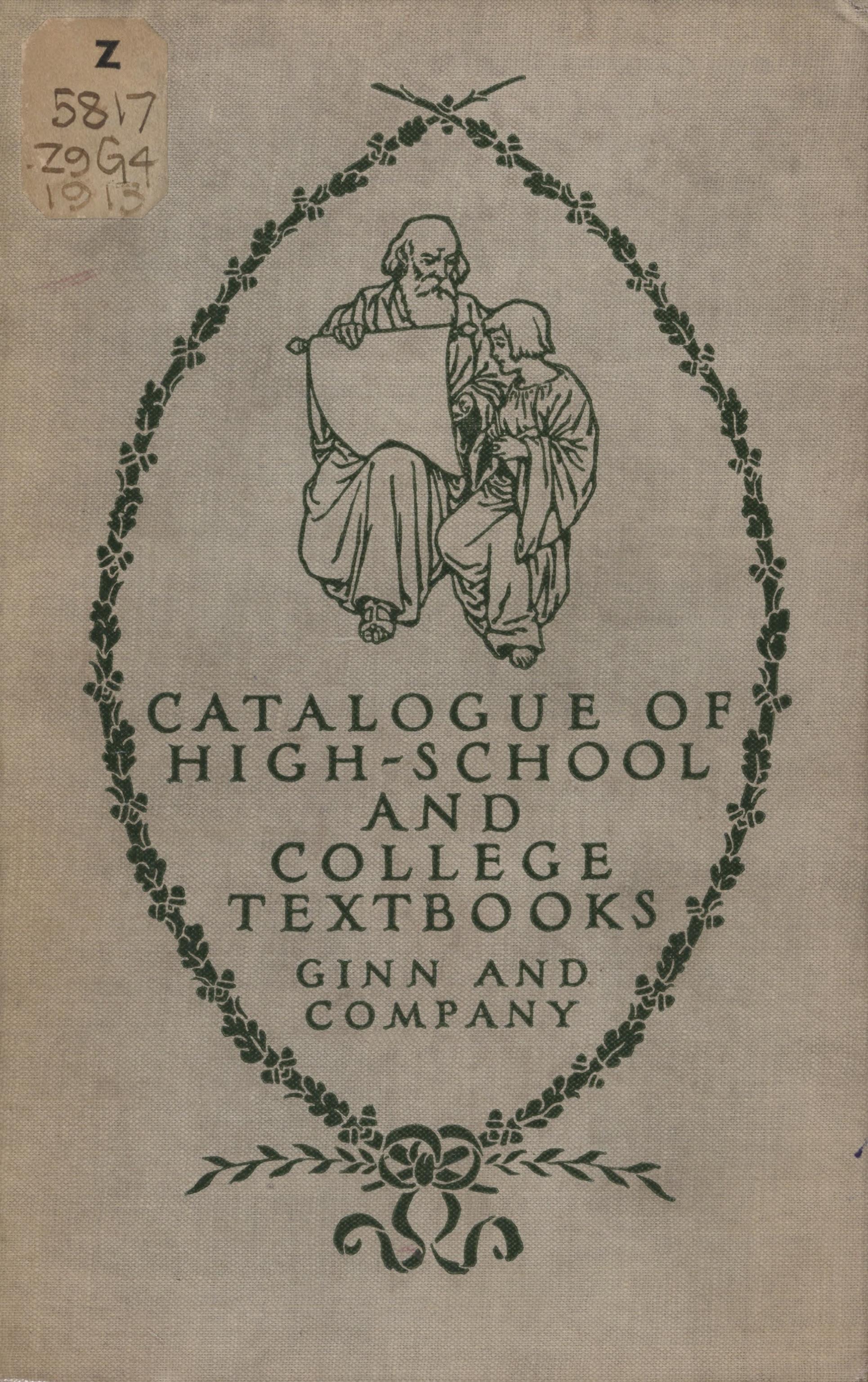

Image: Ginn & Co, F. (1913) Catalogue of High-School and College Textbooks. [Boston, New York etc. Ginn and company] [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/13009453/.

Working with Secondary Sources

This entry was created in collaboration with TPS Consortium Member,  Kristin Mann

. Kristin is a historian who teaches history and Methods of History and Social Science education courses at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. I asked her to provide feedback on my album and she gave me some suggestions from her undergraduate history courses for introducing students to historiographical debates and different approaches to historical interpretation.

Kristin Mann

. Kristin is a historian who teaches history and Methods of History and Social Science education courses at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock. I asked her to provide feedback on my album and she gave me some suggestions from her undergraduate history courses for introducing students to historiographical debates and different approaches to historical interpretation.

Kristin offered this advice: "I think that using older digitized books that narrate history is another way of getting at historiographical approaches, or using excerpts from history texts for different audiences or written from particular perspectives. Especially when we use footnoted books and then trace the sources backwards, we can see what types of sources are used to build an argument."

She developed the following inquiry module to introduce students to historiography, differing secondary source interpretations, and different forms of evidence: How should we characterize the missions of Northern New Spain?

More resources for identifying historiographical debates:

- History Compass: An open-source journal that provides peer-reviewed summaries of current research

- Oxford Bibliographies: Provides research guides for various topics

- "A Study in Second Class Citizenship": Race, Urban Development, and Little Rock's Gillam Park, 1934-2004 by John A. Kirk: An article used by Kristin in her historical methods class

The primary source, Catalogue of High-School and College Textbooks, illustrates how the Library's online collections can be used to locate sources that contain changing historical narratives across time. Additionally, this source can be used to introduce preservice social studies teachers to the historical read as a historical thinking process. Historical thinking is not neutral or universal. Historians draw on different theoretical and methodological approaches when studying the past and historical interpretations change across time. It is important to help students de- and re-construct narratives in academic and popular historical culture. By analyzing the cover of this catalogue, students can make inferences about whose history is represented in early 20th century textbooks and how historians during this time period approached the study of the past.

Reference link: https://www.loc.gov/item/13009453/