Peter Pappas

has done some great posts introducing the possibilities offered by Generative Artificial Intelligence like Chat GPT and other platforms to teachers. Now I have a question of interest to everyone teaching English Learners that I hope he and the other mentors -- and other teachers in the classroom -- can answer.

Peter Pappas

has done some great posts introducing the possibilities offered by Generative Artificial Intelligence like Chat GPT and other platforms to teachers. Now I have a question of interest to everyone teaching English Learners that I hope he and the other mentors -- and other teachers in the classroom -- can answer.

How do we set up a glossary generator that uses images from Library of Congress primary sources? And provides a link to the citation? And, failing good LoC images, draws from other .gov and .edu reliable sources, and also provides those source links? Bilingual Education/ESL

In a perfect world, the images selected would be iconic ones that would contribute to students' background knowledge familiarity.

The TPS project, Multilingual Learner Collaborations, by the Massachusetts Council for the Social Studies has produced a series of instructional tools to support access to Document-Based Questions for Multilingual Learners. Among the tools is a series of instructional slides, as well as direct handouts to guide teachers in this work.

Among the suggestions is to use available Artificial Intelligence tools to create first drafts of essays that use the same argument structure as the assigned essay to offer as examples for students.

They also have a model to show how vocabulary can be introduced visually on slides, and again in a notecatcher that students use to find examples of that vocabulary in the primary sources or background essay (see image, from the Emerging America Teaching Resources searchable database).

I am curious about whether we can use AI to help make a draft of similar picture-illustrated vocabulary lists.

Any suggestions, tech-savvy teachers and librarians?

James Thompson, an undergraduate summer intern at the Library of Congress, has featured the materials that LOC curator Nanette Gibbs curated over eight years concerning arithmetic all around the world. He writes in a delightful post about his summer,.

- My first task was to assist in the curation and creation of materials for a series of Teacher’s Workshops in which the Hispanic Reading Room would participate. I was presented with a depth of materials that Nanette had curated over eight years concerning arithmetic all around the world, each book shaped by the language and culture for which it was produced. These books went largely untouched for about half a century, and our job was to make them useful and exciting to modern educators. Here, Nanette urged me to think contextually – imploring me to step outside of our division or just the collection we had gathered, and instead make use of the depth of information that we have in the multiple research divisions. Diving headfirst into the collection, we were able to find a plethora of materials that could serve as aids to Spanish language learners as well as students learning English as a second language. Reviewing the books, we found that many of the word problems corresponded to goals set by state standards of education, and even SAT practice problems in books meant for elementary age students.

Still, we thought there could be more, so we sought to, once again, think contextually, and remembered the counting songs of our youth – “One potato, two potato, three potato, four” and jump rope rhymes that counted how many doctors it would take to revive Cinderella after her mistaken romantic encounter with a snake. So, we went downstairs from the Hispanic Reading Room to the American Folklife Center where their team was eager and knowledgeable about finding some materials that could aid us in our search. To our luck, their collections contain multitudes of children’s games from over the ages and throughout the world – many of them having to do with elements of counting in various intervals. We were even able to find recordings made in my home-state of Texas during the early 1930s of Spanish counting songs!

I just saw a post in the newsletter of the Office of English Language Acquisition (see text below) and learned that there is a National SPANISH Spelling Bee! This opens so many avenues for teaching ideas, both in the the direction of primary sources about spelling bees, and in planning participatory activities for students spelling in English and in other languages.

The Wikipedia entry on the spelling bee offers some delightful connection points: the linguistic association with work "bees," the 19th century spelling bees in schools and the National Education Association's "first national spelling bee" held at its convention at which Marie Bolden, a Black girl from Cleveland, OH was named champion.

The entry then goes on to list spelling bees held in countries other than the USA, both in English and in other languages.

Spelling bees, in English and in students' home languages, are a lesson activity option with great opportunities for being a bit silly, whether students are teamed up or competing individually. They also, of course, offer lots of engaging primary source connections.

- Winners in National Spelling Bee received by President Coolidge. 1927 https://lccn.loc.gov/

2016890661. (the image doesn't capture the silly mood I was going for, but maybe that's a feature to have fun with): -

-

The Massachusetts Council for the Social Studies has a TPS project that this year is overseeing a collaboration between Multilingual Learner specialists and History teacher to demonstrate HOW to scaffold a document-based-question (DBQ) with 10 primary sources for beginning and intermediate English Learners.

Primary Sources and Political Parties: Reading Complex Texts, a blog post by  Colleen Smith

published on April 30, 2024 addresses the challenge, for all students, of tackling a text that is complex. As she says,

Colleen Smith

published on April 30, 2024 addresses the challenge, for all students, of tackling a text that is complex. As she says,

- "While students may grumble at deciphering language used at a different time and place, spending time on that task helps students build vocabulary, construct meaning, and often form new questions that spark additional inquiry."

I have been thinking a lot about complex text and students who are learning new skills and content in what is for them an ADDITIONAL language. This post brought me freshly face-to-face with how challenging that can be.

To quote from George Washington's letter to Alexander Hamilton,

- "Differences in political opinions are as unavoidable as, to a certain point, they may, perhaps, be necessary; but it is exceedingly to be regretted that subjects cannot be discussed with temper on the one hand, or decisions submitted to without having the motives which led to them improperly implicated on the other: and this regret borders on chagrin when we find that men of abilities, zealous patriots, having the same general objects in view, and the same upright intentions to prosecute them, will not exercise more charity in deciding on the opinions and actions of one another."

On the one hand, language barriers should not dissuade teachers from challenging students with the grade level tasks of inquiry, analysis, and having age-appropriate discussions. This may mean translating, trans-languaging (encouraging students to use their other language skills in reading, discussing, and writing their ideas down), and simplifying texts to get across the central ideas.

- (e.g. what happens when political disagreements are expressed by saying that anyone who does not agree with them is untrustworthy?)

On the other hand, a 20-year veteran history teacher who co-leads the project PLC notes that she often has multilingual students in high school, currently or previously classed as ELLs, who have NEVER ever been presented with a primary source, only a pre-digested summary. Dr Lily K. Filmore evocatively named the "juicy sentence" that has complexity, richness, and variation in structure. Not diving into juicy sentences deprives students of...well, the juice!

I encourage TPS Network readers to read Colleen Smith's post to see how she suggests guiding students through the reading of George Washington's letter.

And of course, please share any strategies you might add, especially with multilingual learners, to support increasing student comfort with complex texts!

I want to both highlight and create a searchable bookmark here in the TPS Teachers Network for the April 18, 2024 blog post, Afghanistan Reflected in the Collections at the Library of Congress. A guest post by Iranic World Specialist (Iranic is a new word for me) Hirad Dinavari, it features beautiful photos of manuscript fragments and caligraphy, and also highlights more recent multimedia and multilingual sources.

It provides a mini-historical overview of Afghanistan, and notes:

- The African and Middle Eastern Division (AMED) at the Library of Congress has been active in expanding and enhancing its collection of Afghan materials, including providing digital access to Afghan related resources. Such materials include illuminated manuscripts and a unique collection of Persian and Pashto language lithographs and early imprints from Afghanistan. Collecting Afghan materials, however, requires looking beyond sources published in native Persian (Dari) and Pashto languages. There is a plethora of sources in various languages such as in English, particularly regarding British and American involvement in Afghanistan, in Russian documenting the Soviet invasion, and Arabic and Urdu content covering religious movements and diaspora refugees in neighboring Pakistan, Iran, the region and around the world.

Check out the multimedia sources below, and consider how you might use these resources for cultural connection and what is termed "culturally sustaining pedagogy," as well as promoting strong research and inquiry skills that take advantage of home language strengths and other knowledge.

Zhvandūn : majallah-i haftagī. Volume 31, Number 49, Saturday, February 23, 1980

(Afghan Life magazine) Featuring Young Women and Men Athletes, Pre-Soviet Invasion Publication). Library of Congress, African and Middle Eastern Division.

Digital Afghanistan:

The Afghan Media Resource Center

(A collection acquired through collaborative effort with Afghan partners featuring 1,175 hours of videotape, 94,651 black & white and color photos and slides, and 356 hours of audio recordings on 40 plus hard drives.) Library of Congress, African and Middle Eastern Division.

(A collection of more than 420 audio recordings documenting Afghan music, folklore, and culture.) Library of Congress, African and Middle Eastern Division.

(A collection of photographs documenting the Anglo-Afghan Wars.) Library of Congress, African and Middle Eastern Division.

I'm searching for some new activities to engage students with primary sources, and came across this one that I like for all sorts of purposes, from Edutopia:

"...students can engage with art and develop literacy at the same time when you give them adjectives and ask them to find a piece of art [or primary source] that fits their word. They can then write the name of, or [draw a sketch, to later] present their artwork and share why they think it’s a good fit for their assigned words. I’ve seen this done masterfully with Apples to Apples: Green Cards."

In the context, this is presented as an option for younger students, but I think it work well as a warm up activity for any age group, and is suited as a multisensory vocabulary solidification activity for multilingual learners.

Are there culturally relevant primary sources that you think could be woven into an engaging learning game for your students?

I just saw an enticing post in the TPS Commons by  AnnMaria Demars

, Want to Make a Game Using LOC Resources?

AnnMaria Demars

, Want to Make a Game Using LOC Resources?

In the post, she writes:

"If you'd be interested in making a game with images and other resources from LOC, we have two options (both free because the platform is in beta and we want feedback). We can easily do games in two languages, but you'd need to provide the translation if the second language isn't Spanish."

Option 1 is to use their accessible coding platform yourself (or have a code-savvy student do it).

Option 2 is "We have interns who are doing demo games using the platform. If you'd like to be paired up with one, you can sign up at the same link and just let me know that's what you want. We can discuss your game and what the interns can do (coding) and what you would need to provide (script and resources to include). Of course, they can only use resources that are not copyrighted."

https://www.7generationgames.com/customized-development/ - it lists costs, but as noted above, they are offering free services right now.

Their page also has links to already created games: https://www.7generationgames.com/products/ which includes several bilingual math games (Spanish-English) with culturally relevant features.

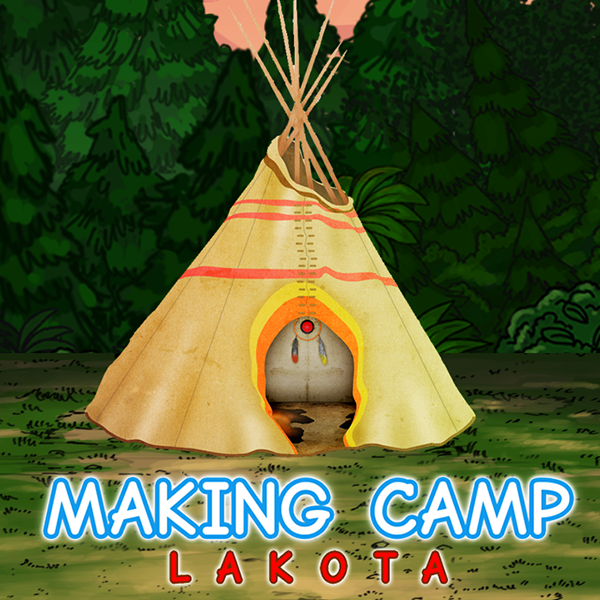

7GenerationGames.com webpage example below:

Games for Underserved U.S. Communities

When it costs $250,000 to make a good educational game, you aren’t going to make one that teaches the Lakota language for the 100,000 Lakota living today or the 1,000,000 Guatemalan immigrants.

Decades of research has shown that students learn better when material is presented in contexts that are familiar to them. Making Camp Lakota, for example, teaches about Lakota history and culture, includes instruction in basic division, with games like “Earn your horse” and can be played in English or Lakota.

Facebook and the Huffington Post. Not where I expect to go for primary sources.

Yet this morning, that's what prompted my journey in search of Library of Congress resources on Kahlil Gibran's writing to young immigrants like himself.

https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdcwdl.wdl_12958/?st=gallery

https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdcwdl.wdl_12958/?st=gallery

The algorithm of Facebook offered me a new page to follow, "English Literature," with an unattributed mini-essay* on Gibran that focused on his experience as an immigrant boy, illustrated by a beautiful, and widely known, portrait. I had not realized that Gibran first came to Massachusetts, my state, and that he had written the words quoted in the essay, "I believe you can say to the founders of this great nation. 'Here I am. A youth. A young tree. Whose roots were plucked from the hills of Lebanon. Yet I am deeply rooted here. And I would be fruitful.'"

I searched the Library of Congress collections, but also in Google, putting in those evocative words as my search term. And I came upon the most wonderful primary source set in an essay from 2017 in the Huffington Post by Magda Abu-Fadil, Kahlil Gibran: Beyond Borders.

In this review of the book Beyond Borders by Gibran's late cousin and his cousin's wife, Abu-Fadil shows the page of the book in which "Gibran's Message To Young Americans of Syrian Origin" is printed, and the cover of the Interlink Press collection of his work, (coincidentally, a Massachusetts publisher that is 7 miles away from where I am writing).

Abu-Fadil provides a Sketchbook self-portrait of Kahlil Gibran herding

sheep in Lebanon, late 1890s (Courtesy Museo

Soumaya, Fundacion Carlos Slim, Mexico City)

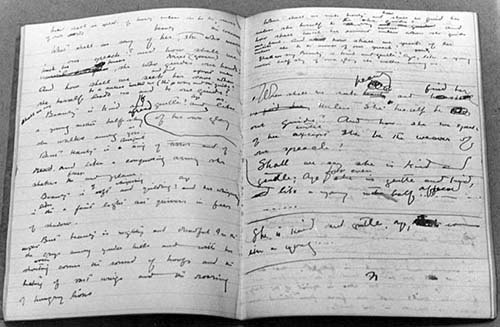

and also

Pages from Kahlil's notebook for "The Prophet" around 1920 (Courtesy

Museo Soumaya).

and

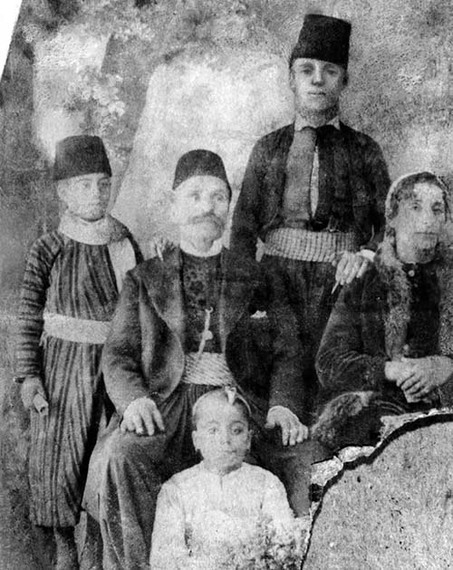

The last portrait of the Gibran family together before their departure

to America in the spring of 1895 (Courtesy Museo Soumaya)

And Abu-Fadil provides her own photograph of the title page of her own copy of the book whose photo I took from the Library of Congress collection at the top of the page. (Along with personal photos of the landscape of Lebanon, and of artwork connected to Gibran's journey as a writer and artist of his time--her essay is rich with visual sources.)

Such a rich teaching set of primary sources! I am grateful to the Facebook post for leading me to the the HuffPost review of the book published in my own backyard. And happy that in the TPS Teachers Network, I have an outlet to share the sources so that perhaps other teachers will find and use these sources when they teach poetry, immigration, and the vital presence of Arab-American members of the US citizenry that can be an inspiration in dark times.

I don't normally write about any commercial products for fear of appearing to endorse them, but Diffit for Teachers has a free-for-teachers version that might be of interest to anyone teaching English language learners. Diffit makes graphic organizers for history learners, too. You can try it for free before committing to any kind of paid package (individual or school subscriptions available).

If you wish to adapt reading levels of texts and other media for your ELL students, below is the Diffit website's general description of ways you might use its product for your students:

Adapt any PDF, text/excerpt, Article URL or YouTube video for any reading level or language - to help all students access the content you’re teaching. Great for:

-

An article you found and want to use for your lesson, but is too hard - for some (or all) of your readers

-

Supporting students learning English

-

Modifications for students with IEPs

-

Challenge for advanced students

-

Enabling all students - regardless of reading level - to access grade level concepts, while providing “just right”, curriculum-aligned readings, vocabulary, comprehension checks, and more.

I would add that primary source descriptions and other Library of Congress content might also be adapted using this tool. Has anyone tried Diffit for Teachers? What other tools do you use for adapting primary sources for your ELL students?

Spanish is the language spoken by many of the multilingual learners in classrooms in many regions of the USA. Getting students to share their own story, and ask older generations to share the stories of their own experience, are often part of language-learning classroom and social studies classroom activities

A bilingual English and Spanish source set on one family's experience, making explicit the importance of family stories as history, with audio clips, family photos, posters, and key passages in two languages is a resource I want to share here on the TPS Teachers Network.

Link to StoryMap "Aquí, pero allá"

The storymap was the creation of two Georgetown University graduate students, Tatiana Cherry Santos and Melissa Flores, as their capstone project for Georgetown's School of Foreign Service. The research guide they created was added to guides for all the countries in Latin America, the Caribbean, and Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking Europe with materials at the Library of Congress: guides.loc.gov/hispanic. There are 47 of them as of now!

In Santos' and Flores's introduction to their work, after telling a bit about their families' reasons for coming to the US from Chile and Brazil, Melissa Flores noted:

- "Our examples are two out of the seventeen countries that comprise Latin America – and that’s not even counting the Caribbean. Despite these “major” differences between how our families got here [exiled from Chile, economic migration from Brazil], their experiences living here are eerily similar. It consists of learning how to speak English, creating community with others that share the same nationality, remaining connected to a “home” country through food, music, and traditions. I’ve learned about my family’s experiences in this country through the countless stories they re-tell, family scenes not much different than the one we have highlighted."

Testimonials

- I love that there is new info on the site daily!

- I had a wonderful time working with the Library of Congress and learning about all of the resources at my fingertips!

- The TPS Teachers Network has an equal exchange of ideas. You know it's not a place where you're being judged.

- My colleagues post incredibly fine resources and ideas....the caliber of the suggestions and resources make me feel that I take a lot from it. It's a takeaway. And I hope that I can give back as much as I get.

- Going into this school year, I have a fantastic new resource for my own instruction and to share with my colleagues!

- I am very glad that I discovered the TPS Teachers Network through RQI. Great resources can be hard to find out there on the internet!